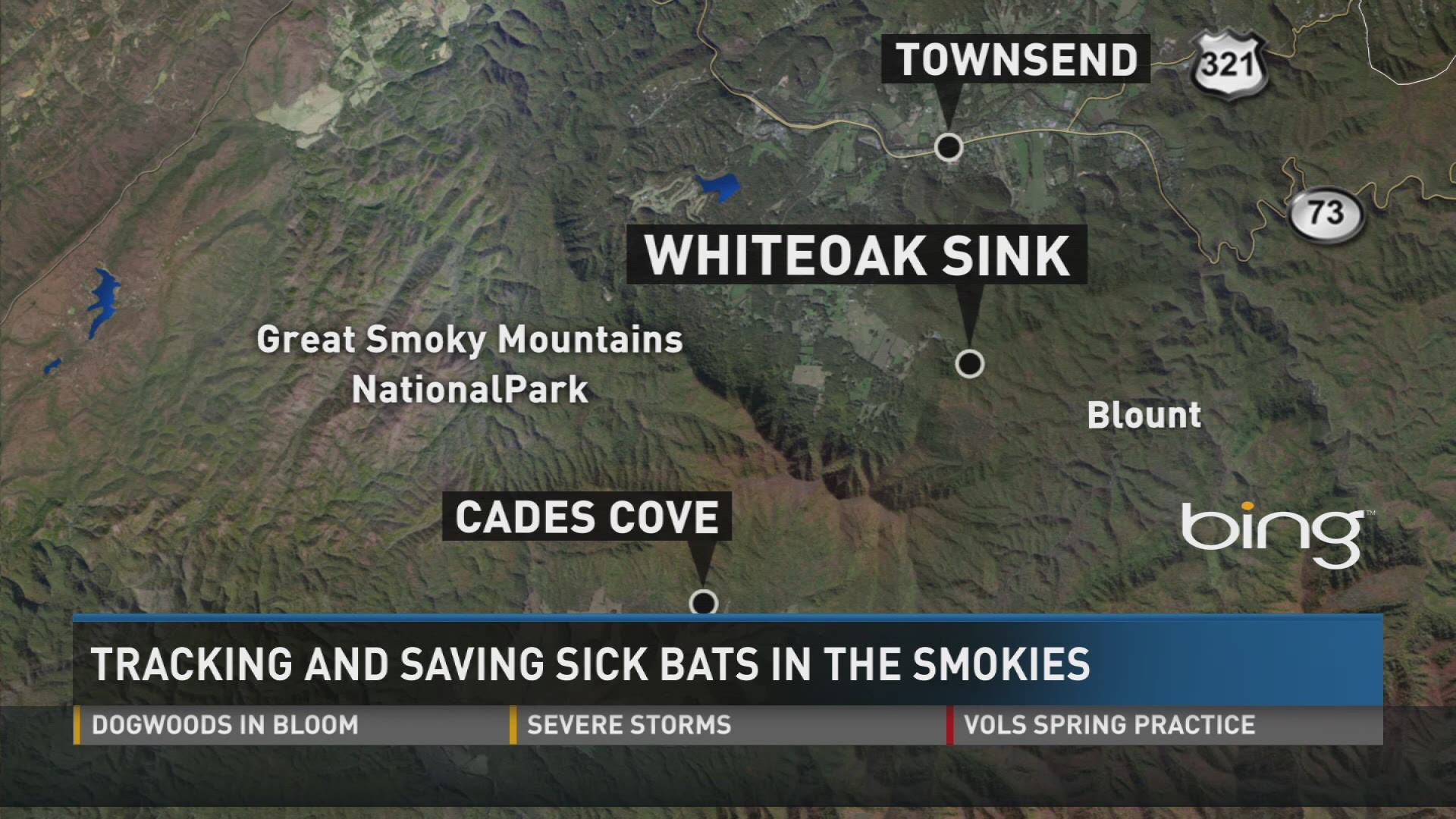

The Great Smoky Mountains is partially re-opening a popular spot for wildflowers, but will continue to limit access because biologists say sick bats are fighting for their lives.

The Whiteoak Sink area will have limited access from April 1 through May 15, especially near the cave where bats are emerging from hibernation. Many are infected with the invasive cave fungus that causes the deadly White Nose Syndrome that has devastated bat populations in recent years.

"We have 12 species of bats in the park. The fungus that causes White Nose Syndrome has been found on seven of those," said Bill Stiver, GSMNP wildlife biologist. "In the last few years, we've seen 88 to 95 percent of the population of many of these species die. Bats usually only have one or two offspring a year, so you're talking about a creature that will take decades for the population to recover."

To measure the number of bats in the park, biologists are listening for the frequency of bats with electronic detectors. The devices have microphones that record the high frequencies that bats emit to "see" at night via echolocation. Each species has a distinctive call. The devices eaves drop on the forest and scientists can later count how many different voices of each type of bat were active.

"And then really see what difference White Nose Syndrome is having on bat populations," said Stiver. "We know our caves are infected with the fungus and we've seen big population declines in all of our caves."

White Nose Syndrome gets its name from the white fungus that grows on bats noses. The infection wakes bats during hibernation. The animals then burn energy and starve when they should be sleeping.

"Bats and bears have a lot in common. If you think about a bear being in its den and constantly waking up, it will burn all of its fat reserves. If it looks for food in the winter, there is none. The same goes for bats," said Stiver. "These area around the caves will have sick bats coming out that may have a chance of surviving if they can find food and not be disturbed. We're just trying to keep some separation between bats and people. Anything can cause [bats] to burn up more calories and end up dying, so we're trying to err on the side of the species."

The fungus that causes White Nose Syndrome is not harmful to humans. However, bats suffering from the syndrome show the same symptoms as a bat infected with rabies.

"They're both sick on the ground flopping around. So we're trying to keep some separation for public health," said Stiver.

White Nose Syndrome originated in the northeastern United States and has slowly spread south and west. For now, the fungus has mostly been confined to states east of the Rocky Mountains, although it has also appeared in one area of Washington State.

"That's another reason people need to stay out of these closed caves. We know people are helping spread the fungus. If we have a visitor who goes into one of our caves and gets these spores on their clothing or shoes, they could transfer it to California," said Stiver.

While there are anti-fungal chemicals that could help the bats, there is nothing that specifically targets the fungus that causes White Nose Syndrome. The chemicals would also destroy native fungi that are part of the ecosystem in local caves.

For now, biologists say the best solution is to continue research and limit interaction with people to give sick bats a fighting chance to strengthen their frequency.

"Some of these species are already endangered and we have the potential to lose them. If you lose them, you never get them back," said Stiver.

Bats are vital natural predators of mosquitoes and agricultural pests. A University of Tennessee study says the loss of bats in North America in agriculture could have an economic impact ranging from $3.7 billion to $53 billion a year.